What Is Your Language Level?

And why talking about your language level is not useful

The CEFR, or Common European Frame of Reference, is a scale of language learning ability levels. It is designed to be language-neutral — that is, it doesn’t differentiate between the difficulty of German’s declensions, or English’s phrasal verbs, or Italian’s use of the subjunctive. It is written based on what the speaker is able to accomplish in that language.

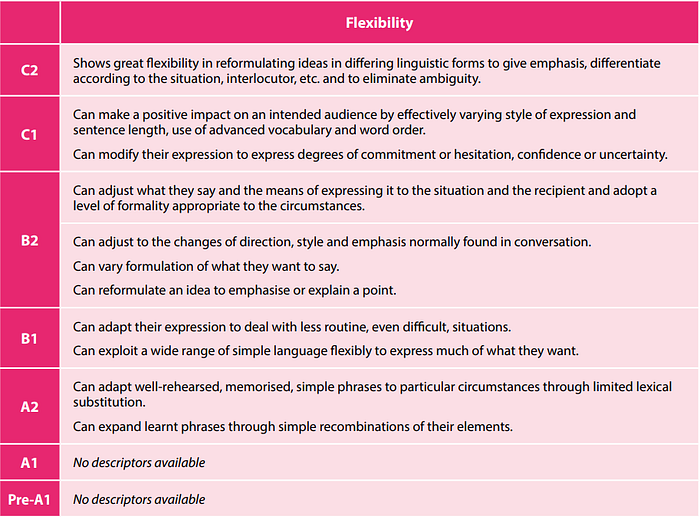

There are six levels: A1 and A2 (beginner), B1 and B2 (intermediate), and C1 and C2 (mastery). Native speakers, according to the CEFR, are not on this scale (though they are commonly referred to as C2). Below is an example of how the CEFR rates a language learner’s ability to listen to someone who is talking to them.

The organization that publishes the CEFR describes moving between the levels as gradual, like the way a rainbow’s colors blend together. I’ll add that a language learner can feel like they shift on the scale from day to day, some days feeling alert and capable, and other days slow and forgetful.

The document in the link above has over 150 pages full of charts like this. The levels distinguish between concepts like:

- the ability to listen in a crowded room, with eye contact, with street noise;

- the ability to write stories creatively;

- the speaker’s ease of producing speech;

- the ability to discern different accents, regional slang, etc.;

- what range of topics that the speaker can discuss, like food and drink, or current events;

- use of temporal discussion like daily routine, past experiences and future plans, and conditionals, hopes, and regrets.

The committee also designs hypothetical language profiles, for example, which abilities you might look for in a job applicant — whether they need to be excellent readers and only passable at daily conversation, or able to make presentations, or even listen to difficult presentations themselves.

The problem in discussing one’s language level is when people are quick to say, for example, “I am C1 in French,” because they’re doing exercises from a “C1 French” textbook — or worse, because they’re 80% of the way through their Duolingo trees (more on that another week). This ignores a wide breadth of ability levels, and perhaps optimistically looks at one’s abilities from only a favored aspect (perhaps they listen to difficult podcasts all the time, but can barely speak — or even, are illiterate).

Sometimes I talk about being “fluent at your level” which confuses people because they understand “fluent” to mean “speaking at the highest level,” C1 or C2. And yes, that is how it is most commonly taken. But at its core, “fluent” just means, “it flows.” Fluency is a skill, like listening or reading. If your speech keeps flowing without pauses, you sound more natural.

Fluency takes a lot of practice, but doesn’t have any anything to do with traditional studying. You might be really fluent at telling people what you are doing right now, but you pause as soon as you have to ask a question, change tense, or even change your mind (as native speakers will commonly do, mid-sentence).

If you’re someone who speaks fluently, you might be able to describe your dad’s sister, where she went on vacation, and the things she saw while she was there. If you’re missing the word for “aunt”, or “travel”, or “sightseeing” that doesn’t knock you down a level — you’re still fluent in a way that you can chat effectively without sounding lost. You just have a lower level of vocabulary (something much easier to improve on).

On the other hand, maybe you’ve progressed pretty far through Duolingo or a set of 2,000 most common words flashcards. You might be able to express a wide range a lot of things. Maybe you have to stop and think all the time because putting the “me” in front of the “he asked” still feels strange (“He asked me” → “me preguntó”, sort of “backwards” to English speakers)… that’s fine — it doesn’t mean you don’t know the language. It just means it doesn’t flow out of your mouth yet.

None of this is to say that one category (vocabulary, grammar, listening, fluency, creativity, conversing) is any more or less important. What’s important is what the language learner’s needs are, and how well they want to be able to connect to their community, perform at their job, or whatever else their goals are.

When people speak about their level, they tend to optimistically state the highest material they are scratching the surface of, which can lead to frustration when they are not at that level across the board. While it is not necessary to rate oneself across 150 pages of CEFR charts, a general knowledge of:

“I’m low B1 in fluency because I pause a lot, and I don’t really use the words, ‘well’, ‘so’, ‘like’, ‘I mean’ when I’m thinking to fill the pauses,”

That means maybe that’s something you’d like to practice inserting in your speech. Or,

“I chat with locals all the time, but I have to have eye contact and a quiet environment… and my personal vocabulary is super limited,”

Then maybe you could watch more TV in the target language, and add flashcards or take notes when you hear interesting expressions.

That sort of self-reflection across a range of skills is actually helpful. Taking an online test that tells you your level in 5 minutes, or listening to a certain green owl… probably not so much. But, more on that, and other learning methods, another week.